In this section we will delve into the pathological variations that occur during prostatitis, in those anatomical districts that we talked about in the Anatomy part

Minor acini and canals

Minor acini and canals

The minor canaliculi ,

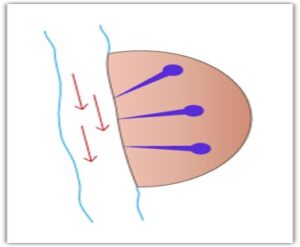

as mentioned above, they serve to convey the prostatic secretion produced in the individual acini into the urethra. The ducts that drain the acini of the periurethral area have a sinuous course, while those coming from the peripheral area have a straight course with an outlet positioned countercurrent to the urinary flow (see figure).

This anatomical situation has the consequence that the periurethral acini will be more easily obstructed in the event of inflammatory processes, due to the irregular course of their channels, and therefore precipitations of various substances can be produced inside them more easily, up to the production of actual stones; the peripheral acini on the other hand, due to the straightness of their canals, will be more subject to the reflux of urine or bacteria from the urethra.

Naturally, all of this has its drawbacks very important therapeutic implications, because if it is true, for example, that periurethral prostatitis can temporarily benefit from vigorous squeezing of the gland, peripheral prostatitis, which due to the almost straight course of the canaliculi, almost never present a situation of stagnation, often do not obtain improvements with this method.

Prostatic urethral reflux

We have introduced, speaking of the peripheral glandular acini, the concept of urethro-prostatic reflux, i.e. the anomalous passage of urine from the urethra into the prostate. For this to happen, however, pathological situations must be created such that the urine, which like any liquid tends to flow where the pressure is lower, finds it convenient to leave the urethra to enter the prostatic tissue.

There are practically two pathological situations:

- In the first we will have an increase in intraurethral pressure due to the narrowing of the urethra:

- due to nerve-based hypertonicity of the periurethral or sphincter muscles,

- or due to stenosis of the canal, on a congenital or acquired basis, as sometimes occurs following previous urethritis, especially gonococcal.

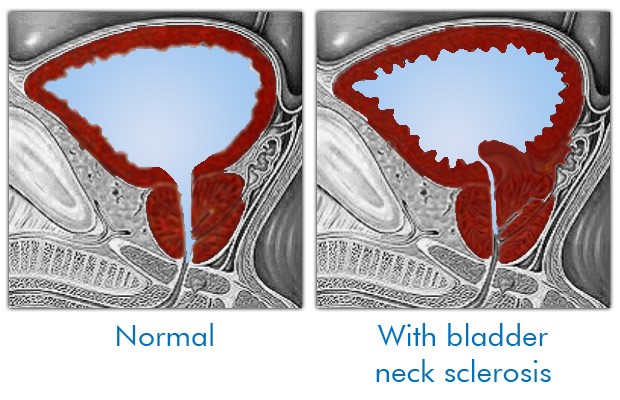

- In the second, however, we will have an alteration of the course of the urethra in its very first portion due to a narrowing or hypoelasticity of the bladder neck, due to a congenital or early acquired condition, called bladder neck sclerosis.

In this case the urine, in the first part of the narrowed prostatic urethra, instead of flowing parallel to the walls, is violently pushed against the posterior wall, which, not being prepared for these high pressures, allows itself to permeate with consequent filtration of the urine in the prostate gland (see figure).

This pathogenetic hypothesis was confirmed with the finding of high urethral closure pressures in so-called abacterial prostatitis which benefited (therapy) from the administration of alpha-blocking drugs combined with antibiotics. Another confirmation of the reflux hypothesis comes from another rather dated but very elegant research (Kirby 1982), in which it was demonstrated that after instilling water with carbon microspheres into the bladders of 10 men with chronic prostatitis and neck sclerosis, these were found in 70% of cases in sections of the prostate taken in the following days during a transurethral resection (TURP).

All the situations described above are easily highlighted with a good transrectal ultrasound in the dynamic voiding phase, which in the first case will show diffusely hyperechoic areas throughout the prostate and in the second case hyperechoic suffusions located in the periurethral area immediately under the bladder neck.

Naturally, as is understandable to anyone, in these two pathological situations it will not be possible to talk about definitive healing of the so-called prostatitis symptoms if the anatomical anomalies that are the primary cause have not also been resolved.

Nonbacterial prostatitis

But if the mechanical cause is often one of the factors that contribute to the onset of acute prostatitis, it is undoubtedly the bacterial infection that produces the real effects.

But how… many people will object to me, don’t abacterial prostatitis also exist?

My answer will be a disappointment for many (for others it will be a confirmation of their ideas)… but abacterial prostatitis, understood as an initial trigger phenomenon,

Ma allora gli esami di laboratorio che spesso dimostrano assenza di batteri nel secreto prostatico, nello sperma o nelle urine sono sbagliati?

THEY PRACTICALLY DO NOT EXIST.

Certainly not but, in this case we are most likely faced with one of these three possibilities:

1) probably the cultures or detection techniques were not adequate to highlight even the so-called bacteria that are difficult to culture such as Chlamydiaceae, Mycoplasmas, Ureaplasmas, Gonococci which all together are nowadays the true causes of around 80% of all acute prostatitis.

2) the bacteria, although existing, remained sequestered within acinar structures obstructed by inflammation. These bacteria sometimes become evident in the urine after careful prostate massage

3) the bacteria really are no longer there as the initial prostatitis has healed and the current cause of the symptoms is now dependent on the resulting spasm of the perineal muscles associated with the aforementioned inflammation of the nerves of the pudendal plexus.

Routes of infection spread

In the case of acute prostatitis, the way in which infecting pathogens can reach the prostatic tissue can be threefold:

ascent along the urethral canal after intercourse (very frequent)

transparietal lymphatic passage from the rectal ampulla (frequent)

arrival by hematogenous route (rare).

Utricle

Another cause of prostatic disorders may derive from that structure left over from embryonic development, called the utricle. As we have already mentioned, the outlet of this formation, if leaking into the urethra, can facilitate the ascent of germs into this “little bag”, thus producing acute or chronic inflammatory situations. Furthermore, even abacterial cystic dilation of the utricle alone can produce “prostatitis-like” symptoms, which can only be resolved with adequate therapy.

Seminal vesicles and ejaculatory ducts

Statistically, their involvement in prostatitis syndromes (vesiculitis) is quite rare, but when this happens it is difficult to eradicate an infection that has affected them due to their particular anatomical conformation.

Speaking of the seminal vesicles we mentioned the ejaculatory ducts through which the sperm drains into the urethra. Sometimes, however, the walls of these channels can become inflamed and stones can form inside, which can be visualized with a typical rosary-bead arrangement. These foreign bodies usually, once formed, produce both painful symptoms during intercourse and a decrease in the quantity of ejaculated sperm, which remaining in the prostate will cause further engorgement, and can sometimes generate hemospermia (blood in the sperm).

Muscles of the perineal floor

The perineal floor, rather than a true flat floor, can be compared to a conical funnel with the base upwards towards the abdomen, with the walls made up of the elevator muscles of the anus and with the bottom vertex open towards the outside from where the urethra and the rectum emerge. The levator ani muscles are not actually made up of a single muscle on each side, but of the set of three well-defined muscle bundles (ischio-coccygeus, ilio-coccygeus, pubo-coccygeus) which, starting from the anal sphincter (hence the name), attach posteriorly to the coccyx and lateral-anteriorly to the bones of the ilium, ischium and pubis.

Why are we talking about these muscles?

Modern theories, as already mentioned above, refer to the chronic spasm of these muscle groups, the real cause of chronic pelvic floor pain syndrome.

But why does spasm cause pain?

If a muscle or one or more muscle groups remain contracted for a long time, biochemical mechanisms are activated which should initially be defensive, but which after a short time instead lead to the local release of pain and inflammation mediators. Thus, in addition to a chemically induced inflammatory reaction, there is an alteration of the local vascular circulation which results in the poor removal of toxic substances physiologically produced by muscular work and which aggravate the spasm itself in a reactive cascade.

But how is this spasm activated?

Simply put, spasm of the perineal muscles can be the result of poorly treated chronic inflammation of the endopelvic organs such as the prostate, vagina, ovaries or rectum-colon, as well as inappropriate surgical interventions. But extensive and well-conducted research carried out in the USA by David Wise, of Stanford University, was able to relate this spasm to causes apparently distant in time from their appearance. In fact, previous episodes of physical or mental abuse suffered as children, or states of bullying during primary or secondary school, but also, incredibly, abnormal maternal behavior, such as making the little child stay on the potty for too long to have a bowel movement, have been highlighted in a statistically significant manner in these patients.

It must also be kept in mind that the muscles of the perineum, as well as for example those of the masticatory muscles, can be a release area for nervous tension, which sometimes act as an irritating thorn triggering the symptoms of muscle spasm. But even all those sexual behaviors that activate a prolonged contraction of the perineal muscles can in themselves trigger a painful reaction or worsening of symptoms. Not to mention that many patients report significant worsening even after simple masturbation. This is due to the fact that the sperm, when passing through the contracted urethral sphincter, causes a lively stretching which leads to a reflex activation of the perineal spasm for hours or days with all the associated pain.

Have you ever wondered why all the symptoms often decrease on holiday?

Because it reduces stress and consequently the tension of the perineal floor!! However, the fact that the symptoms of the disease evolve with the passage of time is an experience more or less known to almost all “chronic prostatitis”.

By investigating the history of symptoms of a prostatitis subject, it is usually possible to distinguish an initial period with initial urethroprostatitic symptoms (even for months), such as urethral burning, urination frequency, etc. which is followed by an evolution characterized by the appearance of symptoms more properly referable to spasm of the perineal floor, such as pain in the perineum, difficult defecation, obstructed urination, painful ejaculation, testicular pain, etc. This can give us a glimpse of how an initial infectious-inflammatory phase of a pelvic organ (bladder or prostate or urethra) is followed by the spastic reaction of the muscles, with the appearance of the much more full-blown chronic pelvic floor pain syndrome.